By Bina Mehta

In Sanskrit, the term “rasa” is a shimmering jewel with a rich multifaceted meaning; it is not something that is understood intellectually but a state to be experienced and felt (bhava). Rasa, in both Ayurveda and Indian artistic tradition, is the essential flavor of experience—the subtle essence that gives life its sensory, emotional, and spiritual meaning. Though the word literally means “juice,” “taste,” “sap,” or “nectar,” its deeper meaning reaches into the emotional body, the psyche, and the soul.

However, every verbal description falls short of what rasa conveys; it is the subtle essence that animates our inner world like a fragrance that arises when body, mind, and spirit align. Rasa is the essence of everything, both physical and metaphysical. As humans, we have both. We are human and divine at the same time. Rasas are strongly interconnected to our relationships with others, the universe, and the divine.

Ayurveda is rooted in the philosophical idea that everything in the world is composed of five elements: earth, water, fire, air, and space, called the Mahabhutas. The five elements combine themselves as triadic bio intelligent forces or doshas (kapha, pitta, vata) that create a foundation for our physical, mental, and spiritual world. The five elements form the world, all food on this planet, and our own bodies, and our food literally forms the physical body.

You are what you eat. Everything in the universe has a quality—in us and in nature. Root vegetables, such as beets, have a heavy quality, and rice has a lighter quality. In addition to flavors, food has more qualitative aspects, called gunas. Every element, doṣha, food, emotion, imbalance—all have their distinct guna qualities. Healing of body, mind, and spirit happens through balancing the gunas.

Rasa carries three interconnected meanings in Ayurvedic philosophy:

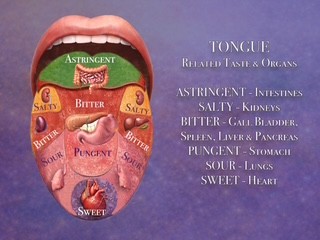

Rasa as the six tastes, or shadrasa: Rasa is the first perception of food through the tongue—madhura (sweet), amla (sour), lavana (salty), katu (pungent), tikta (bitter), kashaya (astringent). Each taste, similarly, to doshas, is composed of two of the five elements, which influence digestion, integration, and assimilation of food in the body.When a meal has been infused with all six flavors, whether it be herbs, vegetables, lentils, meat, spices, etc., the palate will be delighted, and the body will be satiated.However, Ayurveda is a philosophy of wholeness; therefore, the body, mind, and spirit are unified. In this context, digestion has another meaning; that is, digestion of emotions. When all six tastes are balanced and present in a meal, the mind and spirit will also be joyful, and this alchemy makes your heart sing.

Rasa as the first bodily tissue: To eat is human; to digest is divine. In Ayurveda, eating according to your doshas is optimal for health. But without digestion, our bodies cannot access all of the nutrients needed for well-being. Agni, the element of fire, is essential to digestion.

During digestion, food transforms into rasa dhatu, the primary nutritive fluid that nourishes all tissues, organs, and cells. This subtle fluid is the basis for ojas, tejas, and prana—our vitality, radiance, and life force. Without rasa, experience can become dry, rigid, or routine. What we really yearn to tap into is the “juiciness” of life, both literal and figurative.Cultivating juiciness is associated with ojas in Ayurveda, which refers to the purest, most refined essence of everything we eat, think, and experience. In Ayurveda, it is considered the subtle essence of the seven dhatus (body tissues) and the foundation of our immunity, vitality, and emotional resilience. Each dhatu consecutively supports the next dhatu in the order of distilling the essence of ojas, which is key to our radiant health.

After food is digested and filtered through each dhatu, from plasma to blood, muscle, fat, bone, marrow, and reproductive tissue, the finest most delicate part becomes ojas. When you think of ojas, you think of it as an inner glow, your strength and stamina, your emotional steadiness, your capacity of joy, love, and spiritual clarity. Ojas is a life-sustaining nectar that keeps the body healthy, the mind clear, and the spirit grounded. When you see a person full of radiance and joy, you see the distilled essence, or ojas, exuding from their being. They are considered to be healthy and happy individuals who have tapped into the juiciness of life.

If agni is too weak or too strong, undigested or overdigested food turns into ama, whether mentally or physically, which is the sticky waste product that clogs up the flows in our body (lymphatic, circulatory, respiratory, etc.). Therefore, the rasa dhatu needs to be clear of all toxins. Another kind of toxin, garavisha, are environmental toxins such as fertilizers, chemicals, and basic pollution. To battle these toxins, eat mindfully, which results in good digestion that nourishes our tissues and our whole being.

Rasa as emotional flavor: In Ayurveda, every experience carries an emotional rasa, whether pleasant or unpleasant. Sensory impressions move through the body, evoke memory and feeling, and ultimately shape our inner state. Thus, rasa becomes the bridge between senses, mind, and spirit. Ayurveda sees rasa as the essence that nourishes body and consciousness. Rasa is the invisible current that moves us to tears from a piece of music, stirs awe when we behold a sunset, awakens nostalgia from a scent or a fantastic culinary experience, and creates unity between the artist and the audience.

Across Indian traditions, rasa refers to the essential, relishable quality of experience whether physical, emotional, aesthetic, or spiritual. It is a transformational embodied state that brings satisfaction and vitality to food and life. Rasa is a sense of connection to one’s deepest self, a state of complete absorption when the thinking mind stops and pulses of pure feeling arise through body.

The aesthetic essence of emotion in the Indian arts—dance, music, theater, poetry, sculpture, painting, and culinary experience—is rasa, which is evoked in the audience (rasika). Rasa is the transmission, and rasika is the vehicle that receives it. There are nine rasas which are clearly defined vibrational energies that result in nonverbal communication that evokes strong feelings which give rise to all emotions of our human experience. The nine rasas are shringara: love, eroticism, romance; hasya: joy and laughter; karuna: sadness and compassion; raudra: anger, fury, wrath; virya: heroism, valor, courage; bhayanaka: fear, terror; bibhatsa: disgust, aversion, loathing; adbhuta: wonder, amazement, marvel; shanta: peace, tranquility. Each rasa is a portal into self-understanding. When honored, each refines experience into wisdom.

Now, when we talk about feelings, it involves not just our minds, but our five senses: touching, hearing, tasting, seeing, and smelling. The five organs responsible for this consecutively are skin, ears, tongue, eyes, and nose. When we experience feelings, there’s an innate radical unity and connection between body, mind, and spirit, which is physical, psychological, and metaphysical.

There are two kinds of auditory perception in human experience: one is hearing with the ears, which is perception, and the other is listening with the heart, which is the inner knowing. Heart-listening is the language of the soul; it is felt rather than learned. It is tasted by the mind, sensed by the body, and held by the spirit. This state is called Sahaja, the natural, effortless unfolding of one’s uniqueness. When creativity arises from inner silence, it is called pure rasa. This is why great art, profound love, deep meditation, or a simple moment in nature can move us beyond words.

Rasa is multifaceted and multidimensional. To enter its deeper meaning, we must move beyond taste and emotion and step into the realm of sound, where vibration precedes feeling and silence becomes revelation. My visionary teacher, Silvia Nakkach— Grammy-nominated composer, voice culture expert, sound healer and pioneer of Yoga of the Voice—has influenced me for decades through her profound transmission of Indian Raga and Dhrupad singing. Having been immersed in Indian classical music for many years, I came to understand through Silvia that rasa is vibration before it becomes emotion.

For Silvia, sound is not entertainment; it is a vehicle of transformation. Rasa is the flavor of that transformation. In her book, Free Your Voice: Awaken to Life Through Singing, she articulates the inner conditions required to experience the beauty and truth, or satya, of one’s own voice—not as performance but as presence. According to Silvia, the universe is singing itself into being, and the seeker through chanting remembers the ancient melody once again, as a memory of the spiritual.

Silvia describes rasa as the emotional color and flavor carried by sound. When the voice is bathed in devotion, spacious breath, and presence, rasa deepens and becomes a portal to contemplative awareness. Sound then stirs the heart into remembering, reconnecting us with the living divine presence that resides within our unique essence.

For her, rasa is a subtle alchemy that transforms sound into sacred experience. It carries us beyond the concrete and physical into a liminal experience of the soul. She often says that the voice is the “organ and messenger of the soul.”

In this context, liminal refers to the threshold, the space between breaths, the silence between two notes. Silvia teaches that by listening deeply into this silence, one begins to hear rasa and access the divine. Silence tethers us back to the heart, revealing our own unique heart song. Though many may listen to the same music, each person experiences rasa differently, because the way we experience rasa is inherently within each one of us.

Through classical Indian music, Silvia demonstrates how rasa is conveyed, transmitted, and unfolded. As this happens, the ego gently loosens its grip. Attachment to the material realm—I, me, and mine—softens, and we are transported into the cosmic dimension: the source, the divine spark residing within the cave of the heart. She expresses cooperation (resonance) and collaboration with the divine to reveal and express our own essence through song and/or mantra.

She calls this an embodied experience, one in which sound, breath, intention, and emotion are aligned. Through deep listening, rasa vibrates through voice and silence alike, becoming something felt rather than conceptualized.

Silvia also introduces an additional, profound, and powerful dimension of rasa, which she calls Tyāga—the rasa of letting go. Tyāga arises when there is no separation between artist and audience, when the sense of performer and listener dissolves into a single field of awareness. This becomes rasayana, or adaptogens, where healing takes place. In this state of communion with the divine, the personal narrative disappears, the ego is absent, and the question of “Who is singing?” becomes the aspiration, the mystery, and the taste of music.

Tyāga is conscious appreciation without ownership.

There is sound, but no doer.

Expression, but no ego.

Silvia often says that in this is pure rasa, a flash, a moment, “I am not there.”

What remains is intimacy—the deep familiarity of being home.

The word synesthesia mirrors rasa: the merging of sensation, emotion, and essence into a single, lived flavor of being. Synesthesia is a way of perceiving the world in which the senses blend and overlap. Instead of operating separately, one sense naturally evokes another.

For someone experiencing synesthesia:

• sound may have color,

• words may carry texture or taste,

• music may feel like movement or light,

• emotions may appear as shapes or hues.

It is not metaphorical or imagined—it is a genuine sensory experience where perception becomes layered. Synesthesia straddles the human and cosmic world, which Silvia terms as liminal space.

From a poetic and contemplative lens, synesthesia is a reminder that the senses are not isolated. They speak to one another. In moments of deep presence—through music, meditation, art, or love—the boundaries soften, and perception becomes whole. Sound can be seen, silence can be felt, and meaning arises not from thought, but from direct experience.

This is where rasa transcends emotion altogether. While emotions such as joy, sorrow, wonder, or longing belong to everyday experience, rasa is a universal emotion refined and magnified, distilled into a pure feeling beyond language and thought. In Tyāga, even this refinement dissolves, revealing a state in which we are fully tethered to the heart—where truth, consciousness, and bliss converge, known as Satchitananda. Silvia teaches that this state of Satchitananda is beauty itself—or God, the Source, the divine—and that beauty that is not duty.

Rasa restores presence and essence. It invites us to savor, to listen with the heart, to honor our emotional intelligence, and to reconnect with our authentic self. and to experience beauty beyond words. Rasa is where the human and the divine meet, where art and soul kiss, where breath becomes poetry, and where devotion is not sought outward but remembered inward.

This ancient Indian art—carried through music, dance, storytelling, and even culinary tradition for millennia—continues to callus home. Rasa is the essential theory of Indian art, speaking of the pure delight that arises when beauty is encountered without grasping. Rasa is experienced only by the heart.

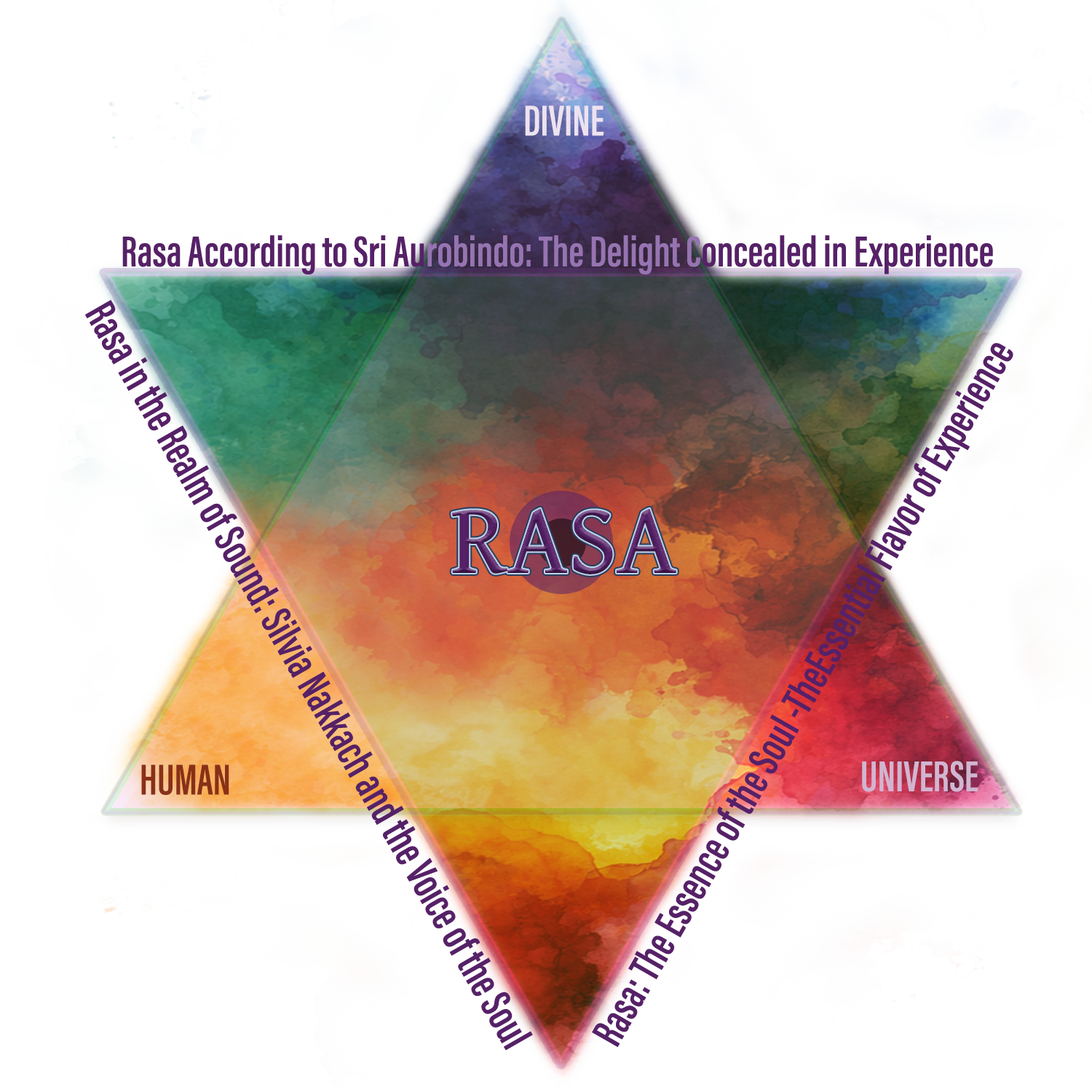

Rasa According to Sri Aurobindo: The Delight Concealed in Experience

Sri Aurobindo offers one of the most spiritually expansive interpretations of rasa. For him, rasa is not limited to aesthetic emotion or sensory pleasure; it is the ultimate delight of existence itself. On the highest level, rasa is Ānanda—the divine bliss that permeates and sustains all creation.

The Taittirīya Upaniṣhad suggests Rasa is God:

“Raso vai saḥ” — Truly, the divine is rasa.

This profound statement reveals an intimate vision of the Absolute. Rather than describing Brahman as an abstract principle or distant reality, the sages point to something profoundly experiential: the divine is that which is tasted, relished, and lived. Existence itself carries flavor and delight.

This means the divine is the enjoyer of the ultimate essence–the rapture of being itself. In other words, the divine is Satchidananda. Sri Aurobindo takes this Upanishadic insight and expands it into a cosmic and evolutionary vision of consciousness. One of the most luminous teachings on rasa appears in the Taittirīya Upanishad where sages speak not of the doctrine but intimacy, which is that atman is born of Ananda, bliss. Then they offer a simple but radical declaration, raso vai sah, that divine is rasa. In this teaching, the universe does not rise from thought or command, but from flavor, from essence from delight. When music dissolves the listener into sound, that is rasa. When love softens hearing and ego disappears, that is rasa.

For him, rasa is not aesthetic emotion of sensory delight, it is delight of existence itself–Ānanda–manifesting through matter, life, mind, spirit, and prana (breath and life force). Raw emotion and devotion (bhava) serve as the doorway, as purified feeling, and rasa is the distilled nectar of that feeling—universal, timeless, and divine. We taste this nectar in fleeting moments throughout our lives, day in and day out; when we are aware that these moments are happening daily, we appreciate them.

In this understanding, rasa is the soul’s response to the divine. It is the subtle vibration that arises when consciousness recognizes itself. Whether an experience is joyful or painful, sweet or bitter, rasa is the concealed delight at its core—the remembrance that we are sparks of the divine participating in a greater play of consciousness.

Aurobindo does not see the world as an illusion to be escaped, but as līlā—a divine play of self-expression. Creation arises from divine delight, and that delight seeks to experience itself through form, movement, and relationship. Rasa, in this sense, is the taste of that play—life tasting itself.

Emotion becomes rasa when it is purified into its essence—when it no longer belongs to “me” or “you,” but to a greater, universal field of consciousness. It is the moment emotion ceases to be personal and becomes archetypal—something the soul recognizes as truth. What I call the subtle experience of rasa, Aurobindo calls the universal aesthetic essence.

Among the nine rasas, Aurobindo places Śānta—peace—as the highest. This is not peace as the absence of difficulty, but peace as fullness: a calm, luminous joy that is not dependent on outer circumstances. This insight aligns seamlessly with Ayurveda, which teaches that the mind naturally rests in clarity and steadiness when nourished by ojas. Peace is not withdrawal from life; it is deep intimacy by engaging with life and all of its challenges.

Aurobindo offers an insight that has stayed with me: “Rasa is the delight of spirit in its own self-expression.” Here, rasa becomes a gateway to higher consciousness. When the ego softens and the personal narrative dissolves, what remains is a quiet familiarity with existence—a feeling of being at home in the world. One is no longer seeking rasa; one is living within it.

In this state, the boundary between the sacred and the ordinary disappears. Cooking, listening, breathing, creating, and loving all become acts of participation in divine delight. Rasa is no longer something to be pursued; it is the atmosphere and space in which we live.

For Aurobindo, rasa matures as consciousness evolves. At the mental level, rasa appears as emotion and aesthetic appreciation. At the psychic level, it becomes devotion, love, and surrender. At the spiritual level, it reveals itself as a calm, luminous joy—a steady sweetness of being that is no longer dependent on outer conditions.

This is where raso vai saḥ finds its fullest expression. The divine is not only the source of rasa; the divine is the relishing itself. When the ego recedes and the personal narrative dissolves, what remains is a quiet intimacy with existence—a familiar, homelike joy. One is no longer seeking rasa; one is living within it.

One Truth, Many Paths

Ayurveda is my foundation, where rasa is nourishment at every level—body, mind, and spirit.

Silvia Nakkach reveals rasa through sound and nāda, showing the voice as the organ of the soul. Nāda is the eternal current of sound, a bridge between absolute silence and creation. Sri Aurobindo reveals rasa as the delight of the divine tasting itself. These are not separate truths, but converging streams. Truth is one, expressed through many lineages.

For me, these paths are not merely philosophical ideas; they are ways of perceiving the world and living with sensitivity, presence, and devotion. To taste life fully, in Sri Aurobindo’s vision, is not indulgence. It is remembrance—the soul recognizing its own essence in the world it inhabits. That recognition is rasa.

Knock, knock.

The divine is knocking on your door.

Are you listening?

Listening with your inner ears?

Seeing with your inner eyes?

Hearing your own unique expression of the heart song?

Sources:

Ayurveda: The Science of Self-Healing by Vasant Lad.

Free Your Voice: Awaken to Life Through Singing by Silvia Nakkach.

Integral Yoga: Sri Aurobindo’s Teaching & Method of Practice by Sri Aurobindo.

Natya Shastra by Bharata Muni with commentary by Abhinavagupta.

Taittirīya Upanishad, a key Upanishad from the Krishna Yajur Veda, found within the Taittiriya Aranyaka.

Turmeric and Spice: Indian Cuisine for the Mind, Body and Spirit by Bina Mehta.

Original images created by Nelda Alvarez.